Other Classic Methods of note:

- Wet Hulling (Giling Basah): Common in Indonesia, this method removes parchment while the bean is still wet, creating earthy, full-bodied profiles.

- Double Washed (Kenya Style): Features an extra fermentation and rinse stage for exceptionally clean, vibrant coffees.

Innovation in Coffee Processing: A Flavor Revolution

If you thought coffee processing was just about drying beans on a patio, buckle up. These new methods are redefining what coffee can taste like. Producers are turning to science and creativity to push boundaries, crafting coffees that blow our minds (and palates). Think of it like a new wave of craft brewing or wine-making, where every step has a purpose and every experiment tells a story.

Mossto: Reclaimed Processing

A natural fermentation method that uses the juice from previously fermented cherries to enrich the next batch. Known as film yeast fermentation, it creates coffees that are deeply complex and flavorful.

Double Anaerobic Fermentation: Two Times the Magic

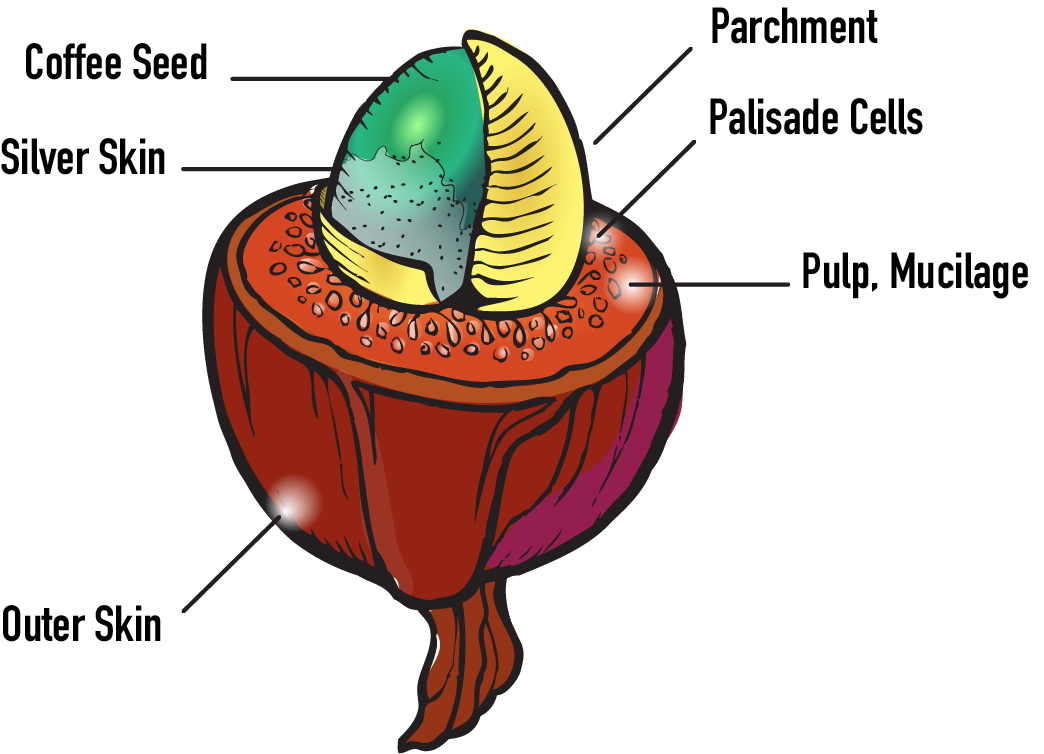

This one's for the fermentation nerds. In Double Anaerobic Fermentation, coffee cherries start by fermenting in an oxygen-free tank. This stage enhances fruity, lactic notes (think yogurt meets tropical fruit). Then, the cherries are pulped, and the mucilage-covered beans go back into another anaerobic environment for a second round. Each stage is carefully timed and monitored to avoid sour flavors while amplifying sweetness and complexity. The result? A cup that’s bold, layered, and smooth—like a well-told story.

Thermal Shock: Science Meets Drama

Ever tried flash-freezing your coffee? Okay, maybe not, but Thermal Shock isn’t far off. It’s all about alternating between hot and cold water during fermentation. Why? The sudden temperature changes stress the coffee at a cellular level, releasing sugars and aromatics you didn’t even know were there. It’s like hitting "shuffle" on your coffee’s flavor playlist: bright, sweet, and unexpectedly smooth.

Thermal Stroke: Coffee's Slow Burn

Thermal Stroke takes the temperature game further by extending it over the drying phase. Think hot and cold cycling, but drawn out over days or even weeks. This extended exposure allows deeper caramelization of sugars and more nuanced flavor development. The result? A coffee with drama, elegance, and the kind of complexity that keeps you coming back for another sip.

Co-Fermentation: Coffee’s Wild Side

What happens when coffee parties with passionfruit, cinnamon, or even pineapple? Co-Fermentation, that’s what. Producers add fruits, spices, or herbs to the mix during fermentation, allowing the coffee to absorb their flavors. The science? These additives bring in their own unique microbial ecosystems, creating a sensory crossover event. Think tropical vibes, floral explosions, or even warm, spicy undertones. It’s coffee reinvented, one experiment at a time.

Koji Processing: Sake, Meet Coffee

This one’s for the culinary crossover fans. Koji Processing borrows its magic from sake brewing. Koji mold (yep, mold) breaks down coffee mucilage with enzymes, unlocking natural sugars and creating savory-sweet umami notes. The result? Coffees that feel like they’ve been aged in the finest barrels, full of intrigue and surprising sweetness.

Hybrid Processes: The Best of Everything

Coffee processing is no longer about sticking to one script. Hybrids mix methods to create something entirely new:

- Supernatural: Start with anaerobic fermentation, then dry the cherries like a natural process. The result? Bold fruity notes with a cleaner finish.

- Hydro-Honey: A honey process with extra rinsing stages. It balances the clarity of a washed coffee with the sweetness of honey.

- Controlled Carbonic Maceration: A mic-drop hybrid that uses precise pH and CO2 controls to finesse every flavor note.

Why These Methods Matter

These innovative methods represent the coffee industry's shift towards a more scientific, precise approach, expanding the boundaries of what coffee can be. Each technique requires a mix of experimentation and understanding of biochemistry, making them accessible primarily to producers with the resources and willingness to take risks.